October 17, 2003

Kabul Letter Number Four

September 2, 2003

Dear Thomas,

At 3:30 this morning, we were woken by a strong but thankfully brief earthquake that shook the houses for about three seconds. I immediately assumed it was a bomb, as I attended the UN security briefing on Sunday where a British military type with a very loud voice informed us that there is gathering evidence that the Taliban (whatever that really means) are approaching the climax of a long-planned terrorist attack on Kabul. He advised us to avoid places where ex-pats gather in large numbers (I need no security officer to tell me that), and to be remain vigilant. There has also been a sudden influx of soldiers onto the streets, checking bags and flagging down cars. Last week the Interior Ministry announced that decorative curtains around the rear windows of cars have been banned, something which causes much grief to Afghans, who take great pride in adorning their vehicles; never have you seen such richly appointed lorries. I have seen drivers protest in vain as soldiers brutally rip out their automobile curtains. I guess this is so forces of darkness cannot seek shelter behind them.

Despite all these omens and portents, things remain calm and generally very pleasant. In fact, the hint of danger in the air is something I am ashamed to realise I quite like, as long as it does not actually involve murderous gangs bursting into my room. The guesthouse I am living in has given me a radio phone with which to report my movements to a central office, but I find this an intolerable invasion of privacy and have decided to pretend that I never go out. My codename is ‘Tango 3’, which is not very inspiring. If it was ‘The Scarlet Pimpernel’ or ‘Darth Vader’ I would certainly use it, but they have not allowed me those. In fact the only other resident of the guesthouse has gone on holiday to Turkey, so I have the whole place to myself, with only Abdul the cook and two cleaning ladies to look after me. They have promised to protect me when the Taliban show up.

In the meantime I have a new student, and I am rather intrigued at the prospect. He is the new Afghan Minister of Agriculture, which sounds harmless, if not dull; but he is also an ex-warlord of the Hazara Tribe, a Mongol people who apparently are descendants of Genghis Khan known particularly for their cruelty in a country that has had more than its share of that. The Minister himself is supposed to be personally responsible for thousands of deaths—in very imaginative ways, particularly by locking people in metal boxes in the desert for a few days, making them turn black. I think I shall correct him sparingly. I wonder when he developed his interest in Agriculture. We have only had one meeting and he seemed perfectly genial, even modest, and very apologetic about his English. I asked him if he had taken lessons before, and he said that he had been too busy fighting—which I felt was a reasonable answer.

I got an email the other day from my Great Uncle Douglas (who had an affair with Melina Mercouri during WWII) and it appears he was stationed on the Khyber Pass in 1946, which is just down the road from here. Apparently the Afghans were considered very wild and dangerous in those days. How times do change...

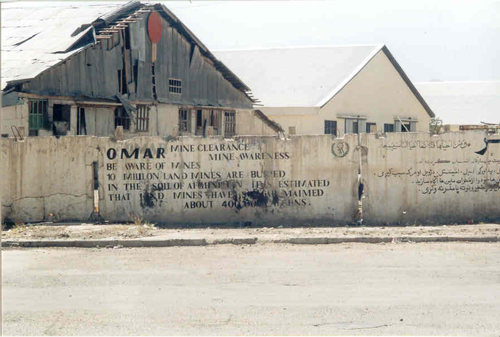

Last week I had a wonderful day travelling to the Panshir Valley, which is about 150 km north of Kabul, and stretches 100 km into the Hindu Kush. It has become famous over the last twenty years for its dogged resistance to the Soviets, who tried on seven separate occasions to subdue it, and also to the Taliban. It is the homeland of the Tajik tribe who are now top dogs in the new Afghanistan, although the Ministries are supposedly shared out fairly between all the factions. I went there with Razoul and one of his cousins (of which he has about fifty); it only took about two and a half hours to get there on a rocket-scarred road. Afghan driving is something to be experienced. It involves giving no quarter and pressing on regardless: quite bracing. The road is lined with white or red markers indicating whether the surrounding area has been cleared of mines or not. Razoul himself worked as a mine clearer for a year, and told me of his terror the first time he located a mine and had to remove the covering earth by hand. He is a very calm and philosophical person, but every so often he will tell me a story which speaks of a very different path through life, like seeing rockets land in the market place, or selling guns when he was eight years old.

The entrance to the valley is very narrow and is still guarded by a burnt-out Soviet tank, a token of the vanity of Ozymandias. Before entering we had to report to a group of stern Tajik soldiers bristling with guns, who were delighted to have their photographs taken. I wore my Afghan clothes for the day (as a security measure), and they all had a good laugh about that, though I think they liked it in fact. The valley itself broadened out into a wide green plain lined with villages of mud houses, with the mighty Panshir River running down the middle. It was a stirring landscape, and there is no question that in the magnificence of the mountains the constant tension of living in Kabul and being caught between such irreconcilable cultures dissolves very noticeably. Working for a western agency is not the way to see Afghanistan. We drove as far as the tomb of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the leader of the Tajik Mujaheddin, who is now the presiding genius of Kabul, and a sort of romantic hero. He was killed by an Al-Qaeda suicide bomber on the 9th September 2001, which is now thought to have been a prelude to the attacks on New York City two days later. It will be marked next week as a national holiday. He is buried on a hillside at the widest point of the valley, a wonderful location for a hero, if that is indeed what he was. Not all agree.

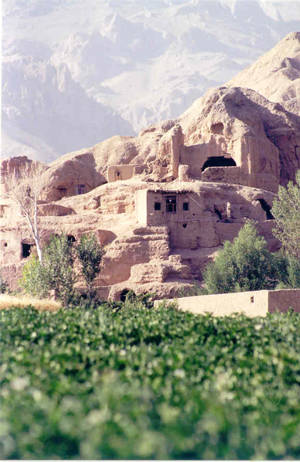

Yesterday I went to visit the mausoleum of the present king’s father, who was (like many Afghans it seems) also assassinated in 1933, which gives you an idea of how long the present man has been king: he was crowned the same year Hitler came to power. The building is on another hillside overlooking Kabul, and must have been quite fine once, but is now terribly damaged by artillery fire. The cemetery around is also full of smashed gravestones and rocket shells dug into the earth. Opposite it lies the Bala Hissar, the old fortification where the British occupying army were all killed in 1847, including their wives and children. A sort of 19th century Twin Towers? The British then came back and pulled it down. The mountains stare down from all directions dry, dusty and ancient, and the mud houses seem to merge into the soil, a perfect example of architecture in harmony with the elements. It a harsh place with no disguise or contrived compensating sweetness. It is very difficult to return from places like this to gatherings of other Europeans—you feel even more insubstantial than usual. In fact, I think Afghans might feel equally diminished in their encounters with westerners. Side by side the two cultures mercilessly expose each other’s failings, and contrive to make the other look foolish, though unfortunately I think we come off worse in the end.

I must emphasize however that my relations with local people are remarkably good. People stop and wave on the way to work, and shout out things like ‘Hello mister!’ and ‘Welcome to Afghanistan!’. I think the bike goes down well, as most foreigners travel in 4x4s with darkened windows. What I like most, however, is my class of architectural restorers. Today I learnt that one of them, Abdul Jalil, is member of a Sufi tariqua, and it comes as no surprise as he has a strikingly serene, wise and selfless manner. After I expressed interest he started to explain the history of Sufism in Afghanistan, starting with a description of the various branches of Islam. The one Shiite in the class (a Hazara, for the Hazara are Shia as well as Mongols) pointed out that he had omitted the Shia, and he very graciously apologised and let the other continue the story. Given that the Tajiks and the Hazara were killing each other until very recently, I found this quite a moving moment. I asked Abdul Jalil whether the Sufis live in communities apart from society, and he said that they deliberately did not: ‘They must live with other people, they must pray at night and work with others during the day. In Islam it is very bad to live apart, it is not the right way.’ So there you are. I also asked him about television, and he said it was possible, but one must be very careful. He himself did not watch it.

He also told me a nice story about Nasruddin Hoja, a mediaeval mullah and wit. A friend found him one night peering at the ground under a gas street lamp. ‘What are you doing, Hoja?’ he asked him. ‘I have lost some money,’ he answered. ‘Oh, where did you lose it?’ he inquired. ‘Over there, in the garden,’ he said. ‘Then why are you looking for it here?’ the other asked in surprise. ‘Because the light is better here,’ said the Hoja. Apparently this illustrates the vanity of looking for the truth by the light of reason alone, for you will look in the wrong place. Abdul Jalil seems to be struck by my interest, and has offered to take me to a meeting of Sufis before I leave, which is what I have been hoping for. This man exudes a strong sense of authenticity, and the others in the class seem to be correspondingly respectful as well as affectionate towards him. I am glad that he is the one who has offered to accompany me. I shall share what I learn with you.

I am now planning to return to Greece overland via Iran. The language I am learning is more or less what they speak there, so it should stand me in good stead. I also have a former student in Iran who has offered to put me up in Tehran. From what I read in the guide books it sounds fascinating, and I know I will like it very much. But there is no guarantee I will be given a visa; unfortunately England is a little too friendly with the Great Satan. We shall see.

Now I must return to my empty guesthouse. I hope all is well with you.

Much love,

Andrew

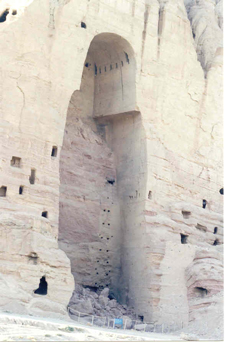

Posted by djsmall at October 17, 2003 02:26 AMI think the photographs in this entry are particularly fine. They were all taken on Andrew's point-and-click. Incredible, eh? Please forgive me, Ashley, but Robyn: maybe Andrew is that older man we used to discuss. What do you think? I wonder what one of those mud huts is going for these days. And why western women don't dress as beautifully as those girls.

Posted by: djsmall at October 17, 2003 02:33 AM