October 18, 2003

Kabul Letter Number Five

September 9, 2003

Dear Thomas,

On Friday last, I was invited by my friend Razoul to his cousin’s engagement party, an entrée into Afghan social life not often granted to foreigners here. I write ‘friend’ because although Razoul started out as my driver, I think I can unexaggeratedly say that he has become a friend in the meantime, especially since I bought the bicycle and he has not had to drive me around Kabul so much. We keep the driving to trips out of town and into the mountains, of which more later. First, the engagement party, which the Afghans call ‘Naamzadi’, which means ‘striking of the name’, because the groom is considered to put his name on the table in token of his good faith. The event took place during the middle of the day (unlike weddings, which are evening affairs) in the fiancé’s father’s home, a large building in the battle-scarred south-west of the city, with countless bullet marks in the plaster and a large hole in the roof where a rocket had fallen some years ago. The first thing to say about all such events is that they are strictly segregated: there is absolutely no meeting between the male and female guests, who in effect conduct two entirely separate celebrations under one roof. Only the groom and very close family members are able to pass into the women’s area at the end of the day, so I cannot tell you what happens at that point. The other male guests (of whom there were about eighty) spend the whole time in the courtyard, while the ladies are indoors, though there was a thick curtain dividing us from a smaller area of the courtyard where the women can come out to dance. Every so often a female head would appear over the top of the curtain, or a slender foot would be seen from under it, enough to remind me again how lovely and arresting Afghan women are, beneath the many layers of material they wear to keep me from this troubling awareness. At the end of my street there is a girls’ school (they were all closed under the Taliban of course) and for much of the day the street is thronged with young women in black trouser suits (shalwar kameez) and white headscarves. I am very struck by the vitality and beauty of Afghan girls. They display much stronger characters than one would expect from a gender who still (in their majority) pass their lives in publicshut away—if you visit someone’s home you will never meet the female members of the family—or completely concealed within a burka.

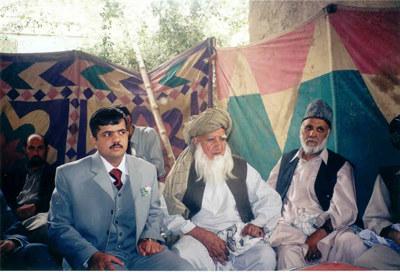

The men celebrate amongst themselves, the family elders presiding in their white turbans or Astrakhan hats, and the younger children in attendance on the rest. A number of the older men wore black eye liner, called ‘sorma’, which is thought to be good for the eyes as well as attractive. Apparently the Taliban all wore it. One of the men also had a carved stick is his pocket which is used to clean the teeth. This practice is not only very good for the gums, I am told, but also a ‘sonat’, a custom practiced by the Prophet himself, and so conducive to virtue as well as health.

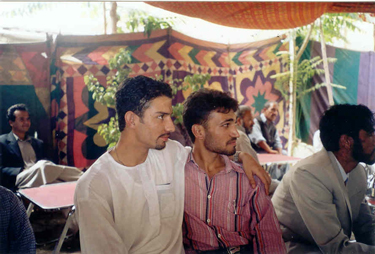

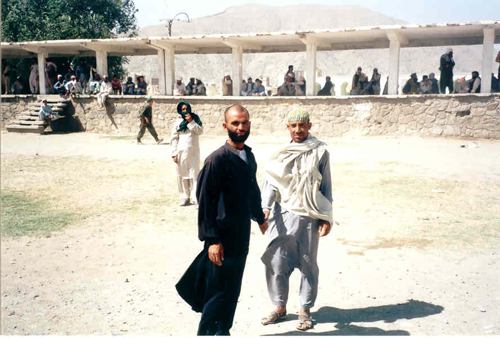

In their behaviour the men provide compensation for the lack of female company, for while all forms of public affection between men and women are absolutely unacceptable here, striking tenderness between men is the norm, to an extent quite unacceptable for us. You will often see Afghan men walking hand in hand; even policemen or soldiers in uniform, or wild bearded gentlemen who surely have several wives waiting to please them at home. Men greet each other with long embraces and kisses on the cheeks. You will see students at the University sitting together and ruffling each other’s hair, even sitting in each other’s laps, with no sense that anything more than friendship is suggested. So it was at this event.

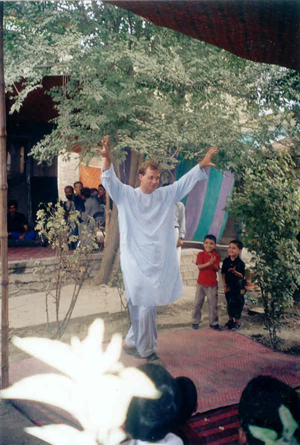

After we had eaten (Afghan food is limited and unadventurous; rice, raisins and chicken or kebab is the rule, products of a frugal way of life), the musicians (drum, harmonium and wailing voice) started up and the dancing begins. Afghan dancing is quite extraordinary, at first very ridiculous and comic, though somehow compelling and ultimately fascinating to watch. The style seems to be very delicate, strange jerking movements with hopping steps, almost like an effeminate form of breakdancing—and once again two men will dance together in an unashamedly intimate fashion. Razoul’s cousin in particular put on a very accomplished display. He is known for his good dancing, though it seemed very strange to me. As I was watching them all in some disbelief, I gradually realised that as the guest I was seriously expected to dance for them myself, an unreasonable expectation, since the whole thing is quite foreign to us, though they are not to know that, I suppose. I spent a good twenty minutes shaking my head, until I realised that they were genuinely disappointed and hurt by my refusal, and so I got up and just threw myself into it, trying to imitate what I had just been watching, and doing a version of Greek dancing at the same time. After about two minutes of inner embarrassment, I became aware that I was in fact a great success. Lots of people gathered round me with smiles and thumbs-up, and suddenly Razoul’s cousin was back on the dance floor with a dance routine that would not look out of place in a club in San Francisco (if you don’t object to the analogy). One or two of the guests got up to throw money over us, which was immediately gathered up by the children, and at the end I was greeted with cheers and pats on the back. You would have been proud of me, and probably embarrassed for me at the same time. Razoul actually took some photographs of this event with my camera, so you can judge it for yourself in due course. (I was, of course, in traditional Afghan dress).

After this foolishness, we sat around a long table to witness the engagement itself. I sat next to one of the two grandfathers present, who are always called on to conduct the ceremony. The table is covered with bouquets of plastic flowers and sweets (‘sweetgiving’ is another name for the ceremony) and then the fiancé is brought in, looking very humble and respectful (though everyone agreed afterwards that he was a very dull looking fellow). One of the elders intoned verses from the Quran, while we all held up our hands in prayer and brushed them over our faces at the end. Then the two grandfathers addressed certain ritual words to each other, before turning to the fiancé and asking him to give his troth. Then everyone stood up and the young man received good wishes and kisses from the whole company--‘Mubarak basha,’ or ‘May it be blessed’—before going indoors to tell the women the good news. I found it moving and replete with meaning; the active involvement of everyone in the ritual was quite tangible; and the fact that the elders rather than the ‘happy couple’ seal the contract seemed to give it more significance. I asked someone there whether love-matches rather than arranged ones are accepted in Afghanistan. He said that they had been for a very long time, but were known to lead much more often to unhappy marriages. I have one student who is 24 years old, whose parents married him off when he was 14, and declares himself very content and proud: he now has four children, the eldest of whom is nine years old. By this reckoning I could be the grandfather. After this ceremony, the future bride and groom are permitted to speak to each other for the first time, though still not without the company of others, and they are able to call the wedding off in the next weeks if the prospect seems too dreadful; though this is a very scandalous course of action, not engaged in lightly.

Afterwards, the guests pick up the plastic bouquets, the music strikes up again, and everyone moves onto the dance floor spinning around with the bouquets held aloft. I joined them. As we were dancing, the curtain in the house overlooking the garden was moved aside, and for the first time I saw the faces of some of the female guests peering out to have a look at the chaps. I waved briefly at them, but was quickly told that that was not permitted, though it was said in a very forgiving way. They know that as a westerner I am on my way to perdition already.

I was privileged enough that same evening to be given the opportunity to compare Afghan celebratory ritual with our own. I was invited to a party given by AWCC, the Afghan mobile phone company (run by foreigners of course), and very reluctantly I went along with a group of young English women I have met here. There was a barrel full of beer, awful canned music, predatory men and graceless women who seemed to screech a lot. After the restraint and meaningfulness of what I had just witnessed, it seemed very hollow, with the drink and the screeching designed to conceal the deceit. I got depressed very soon and left after ten minutes, so I don’t think I shall be invited again. With some sterling exceptions, the banality of many foreign aid workers is one of the many revelations of this visit. One would have thought that danger and humanitarian commitment would suggest rigour of character, but it is not so. I have been to three gatherings of ex-pats since I have been here and each time I have regretted it. Almost everyone is uninteresting, and also uninterested in Afghanistan. They view Afghanistan as a disaster area, a void in desperate need of reform from the West. We should only congratulate ourselves that we are not as they are, and also congratulate ourselves on our freedoms that permit us to do what they can only dream of doing. In fact I find that despite the devastation of the country, we foreigners become more insubstantial when set alongside them. Maybe I idealize, but it is what I feel.

I suppose there are few countries in the world where one can observe Muslim social forms in as unadulterated a form as they are in Afghanistan, especially now that the fall of the Taliban has removed a contrived Puritanism from its practice. I must say that the more I see of it, the more I am impressed by the grace of its ritual and also the kindness and civility with which most people seem to live out its requirements. At its heart is a living adherence to a guiding faith, which enjoys whole-hearted assent by all, so that you truly feel that God is at the centre of men’s occupations. This is shown to me daily in countless different ways. As I said before, I am now living on my own in this guesthouse (a state I am not unused to), but my Afghan acquaintances are very concerned that it will make me ‘deq’ (sad), though it is only for a week. In Afghanistan no one lives alone. It is frowned on for a son ever to leave his father’s home (his wife will come to live with them when he marries), so a wife will live with her husband’s parents. I am sure this can be a very miserable experience, especially for a young girl to find herself at the mercy of her mother-in-law, but it certainly indicates how living alone is considered a state of gross egotism and social failure. In fundamental ways I find social expectations here a deep criticism of my own life, and I am prepared to acknowledge it—the assumption of superiority by most foreigners here is a real blindness, I think. Here, to be unmarried and childless at my age is simply an offence before God and worthy of the mockery of your fellow man. To earn a salary when you have no dependents is also deeply wrong: ‘Who do you earn your money for?’ is a frequent question. Of course I can explain the differences in Western expectations and they will listen indulgently, but they shake their heads in commiseration. The whole concept of one’s ‘personal journey’, to which the West ascribes such value, has no meaning for people here. There is only the one journey, the ‘sunnat’, and your life is assessed according to the extent to which you follow and fulfil its precepts. I come from a broken home, and according to the Afghan, that implies a broken self, for the sins of the fathers are visited upon their sons, and it is right that it should be so. They do not have the same idea of the individual redeeming the many: the people as a whole find salvation, not as individuals, and thus anything that threatens the unity and cohesion of the family is the most sinful and intolerable act there is. It is a hard lesson, but it cannot be evaded here in this context, and I confess that for me it has the savour of truth, though maybe I am also relieved that I am not asked to live it. I don’t know.

On a less elevated level, I have come across some interesting etymological and scatological origins here. First there is the Greek word ‘poustis’ (a homosexual), which comes through Turkish from the Persian preposition ‘pusht’, meaning ‘behind’. I think no further elucidation is required. There is also the well-known Turkish word ‘kro’ meaning ‘a rude and vulgar fellow’, which is derived from the Persian slang ‘kerok’ for ‘large penis’. I find this all very fascinating. My informants are Afghan acquaintances, who seem to laugh about the same things as everyone the world round, and are often quite witty too.

There is much more I would like to tell you about, but I am sure I have tried your patience enough. I am more than happy for you to forward these emails to others, though I don’t know how women would react to the last paragraph. In Afghanistan, vulgarity is strictly a male preserve, as indeed it should be—we are so good at it. And I would not like to be diminished in anyone's eyes. However, if you are able to discuss smegma with Liadain, I suppose I have nothing to worry about. Use your inimitable judgement.

I hope all is well.

Yours,

Andrew

Posted by djsmall at October 18, 2003 12:46 AMThis is my favorite letter so far - the paragraph about living alone was so interesting. And I *wish* I was still innocent enough to be offended by 'large penis'.

Posted by: robyn at October 18, 2003 09:41 PM