October 19, 2003

Tea for a Turk

A friend told me recently that the two parts of the contemporary world he finds most destructive are cigarettes and automobiles. That is funny, because Athens swirls around precisely those two things. Nowadays there probably isn’t a city in the world where cars and fags (in the British sense of the word) don’t dominate, but somehow in Athens both run outrageously rampant. The near-death experience is a daily occurrence to the hapless Athenian pedestrian, and this writer can remember one such occasion in particular, when out of carelessness the tip of his nose was severely wiped by a city bus going fifty down a one-way street. There is a laissez faire quality to Greek driving—something else that puts them solidly in the east, however much they face westward—and for this reason they had the most automobile related deaths in the E.U. until a few years ago, when mandatory seatbelt laws were established. To actually witness a Greek wearing his seatbelt is rare, but somehow on account of these laws Portugal now outkills Greece on the highways.

Not so with cigarettes. Greeks smoke more cigarettes than any other European nation. All around Athens, indoors and out, tobacco is in the air. Office workers smoke at their desks, waiters smoke at their tables, bus drivers smoke behind their wheels, clerks smoke behind their cash registers. People smoke in banks, in post offices and at gas stations. The Greek will not enter a church holding a cigarette, it is true; but he wouldn’t think twice about attending the service from the porch, puffing away with his buddies, perhaps one ear cocked towards the chant drifting out the open door.

Though they would hate to admit it, this widespread habit is another thing that connects the Greeks to their more numerous eastern neighbors. The cigarette was invented by Turkish soldiers, or so the story goes. The Grand Seigneur and his trusty warriors were once again laying siege to Vienna, on one of their many attempts to conquer that city, when after a particularly fierce skirmish, a battalion of Turks realized that their glass pipes had all been broken. Being the fierce fighting men they were, they naturally had copious amounts of tobacco, but now had no way to smoke it. But then one particularly ingenious infidel, deep in thought beside the Danube, rolled a piece of gunpowder paper, stuffed it with his leaf and changed the course of human history.

A group of Turks were tunneling beneath the city walls nearby. Some Austrian bakers were up early, hard at work, when they heard beneath them the pick and ping of axe and shovel. An alarm was sounded, the plot was uncovered and the tunnels were flooded with water. The Ottomans retreated and never returned again. In commemoration of the part they played in the saving of the Empire, and in mockery of the Mohammedan religion, the heroic bakers fashioned a bun in the shape of a crescent. Thus were established in a single day, forged from age-old ethnic warfare, two main components of every European continental’s morning ritual: the cigarette and the croissant.

The Greeks are no strangers to the third component, the indispensable cup of coffee. However, as is expected they no longer give credit where credit is due. In the 1970s, during an American-led military dictatorship, the Colonels, as they were called, made it illegal to label as Τουρκικό, or Turkish, the sort of coffee enjoyed by Greeks the world over, the kind with the grainy mud at the bottom, even though it came to them via the Ottomans. For a while, in a very backwards sort of nationalist confusion, they called their coffee Βυζαντινό, or Byzantine, until it was pointed out that coffee was not invented until the 16th century, long after the end of that glorious empire. In the end, their coffee became Ελληνικό, or Greek, and this is its moniker today. Mischievous visitors to this ancient and prickly land might with a smirk order Τουρκικό, but only a few Greeks would meet their challenge and defend the Hellenic motherland—most would only be confused, so ingrained is their belief in the Greekness of the sludge at the bottom of their mini porcelain cups that they struggle to keep from swallowing.

Ironically, the Turks might just agree with them there. For in the inscrutable workings of ethnic tension and historical reinterpretation, Kemal Ataturk, at the dawn of modern Turkey decided that coffee drinking is Arabic, as it comes from the Yemen, and thus a filthy custom, ill fitting a real Turk. He encouraged instead the drinking of tea, which he saw as quintessentially Turkish—and which, as everyone knows, comes from China.

October 18, 2003

Kabul Letter Number Five

September 9, 2003

Dear Thomas,

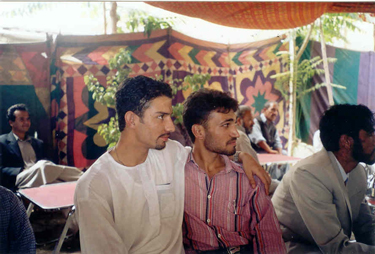

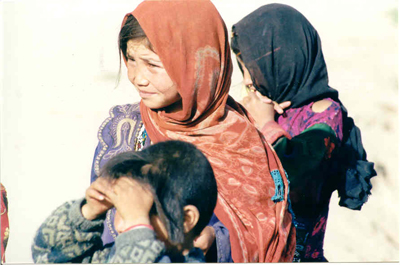

On Friday last, I was invited by my friend Razoul to his cousin’s engagement party, an entrée into Afghan social life not often granted to foreigners here. I write ‘friend’ because although Razoul started out as my driver, I think I can unexaggeratedly say that he has become a friend in the meantime, especially since I bought the bicycle and he has not had to drive me around Kabul so much. We keep the driving to trips out of town and into the mountains, of which more later. First, the engagement party, which the Afghans call ‘Naamzadi’, which means ‘striking of the name’, because the groom is considered to put his name on the table in token of his good faith. The event took place during the middle of the day (unlike weddings, which are evening affairs) in the fiancé’s father’s home, a large building in the battle-scarred south-west of the city, with countless bullet marks in the plaster and a large hole in the roof where a rocket had fallen some years ago. The first thing to say about all such events is that they are strictly segregated: there is absolutely no meeting between the male and female guests, who in effect conduct two entirely separate celebrations under one roof. Only the groom and very close family members are able to pass into the women’s area at the end of the day, so I cannot tell you what happens at that point. The other male guests (of whom there were about eighty) spend the whole time in the courtyard, while the ladies are indoors, though there was a thick curtain dividing us from a smaller area of the courtyard where the women can come out to dance. Every so often a female head would appear over the top of the curtain, or a slender foot would be seen from under it, enough to remind me again how lovely and arresting Afghan women are, beneath the many layers of material they wear to keep me from this troubling awareness. At the end of my street there is a girls’ school (they were all closed under the Taliban of course) and for much of the day the street is thronged with young women in black trouser suits (shalwar kameez) and white headscarves. I am very struck by the vitality and beauty of Afghan girls. They display much stronger characters than one would expect from a gender who still (in their majority) pass their lives in publicshut away—if you visit someone’s home you will never meet the female members of the family—or completely concealed within a burka.

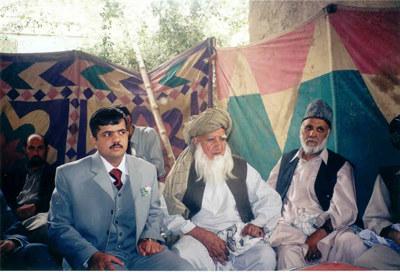

The men celebrate amongst themselves, the family elders presiding in their white turbans or Astrakhan hats, and the younger children in attendance on the rest. A number of the older men wore black eye liner, called ‘sorma’, which is thought to be good for the eyes as well as attractive. Apparently the Taliban all wore it. One of the men also had a carved stick is his pocket which is used to clean the teeth. This practice is not only very good for the gums, I am told, but also a ‘sonat’, a custom practiced by the Prophet himself, and so conducive to virtue as well as health.

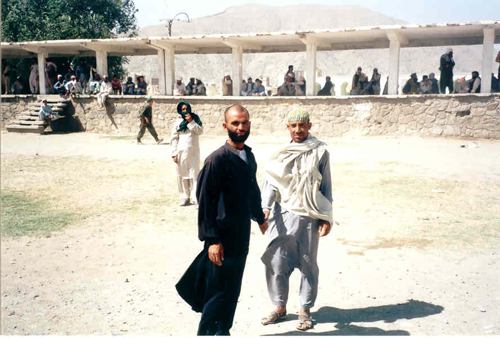

In their behaviour the men provide compensation for the lack of female company, for while all forms of public affection between men and women are absolutely unacceptable here, striking tenderness between men is the norm, to an extent quite unacceptable for us. You will often see Afghan men walking hand in hand; even policemen or soldiers in uniform, or wild bearded gentlemen who surely have several wives waiting to please them at home. Men greet each other with long embraces and kisses on the cheeks. You will see students at the University sitting together and ruffling each other’s hair, even sitting in each other’s laps, with no sense that anything more than friendship is suggested. So it was at this event.

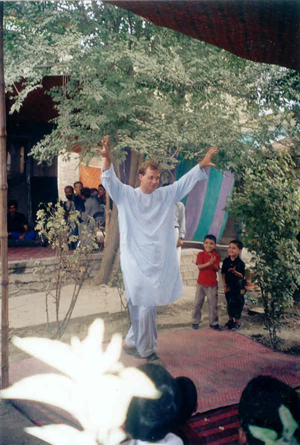

After we had eaten (Afghan food is limited and unadventurous; rice, raisins and chicken or kebab is the rule, products of a frugal way of life), the musicians (drum, harmonium and wailing voice) started up and the dancing begins. Afghan dancing is quite extraordinary, at first very ridiculous and comic, though somehow compelling and ultimately fascinating to watch. The style seems to be very delicate, strange jerking movements with hopping steps, almost like an effeminate form of breakdancing—and once again two men will dance together in an unashamedly intimate fashion. Razoul’s cousin in particular put on a very accomplished display. He is known for his good dancing, though it seemed very strange to me. As I was watching them all in some disbelief, I gradually realised that as the guest I was seriously expected to dance for them myself, an unreasonable expectation, since the whole thing is quite foreign to us, though they are not to know that, I suppose. I spent a good twenty minutes shaking my head, until I realised that they were genuinely disappointed and hurt by my refusal, and so I got up and just threw myself into it, trying to imitate what I had just been watching, and doing a version of Greek dancing at the same time. After about two minutes of inner embarrassment, I became aware that I was in fact a great success. Lots of people gathered round me with smiles and thumbs-up, and suddenly Razoul’s cousin was back on the dance floor with a dance routine that would not look out of place in a club in San Francisco (if you don’t object to the analogy). One or two of the guests got up to throw money over us, which was immediately gathered up by the children, and at the end I was greeted with cheers and pats on the back. You would have been proud of me, and probably embarrassed for me at the same time. Razoul actually took some photographs of this event with my camera, so you can judge it for yourself in due course. (I was, of course, in traditional Afghan dress).

After this foolishness, we sat around a long table to witness the engagement itself. I sat next to one of the two grandfathers present, who are always called on to conduct the ceremony. The table is covered with bouquets of plastic flowers and sweets (‘sweetgiving’ is another name for the ceremony) and then the fiancé is brought in, looking very humble and respectful (though everyone agreed afterwards that he was a very dull looking fellow). One of the elders intoned verses from the Quran, while we all held up our hands in prayer and brushed them over our faces at the end. Then the two grandfathers addressed certain ritual words to each other, before turning to the fiancé and asking him to give his troth. Then everyone stood up and the young man received good wishes and kisses from the whole company--‘Mubarak basha,’ or ‘May it be blessed’—before going indoors to tell the women the good news. I found it moving and replete with meaning; the active involvement of everyone in the ritual was quite tangible; and the fact that the elders rather than the ‘happy couple’ seal the contract seemed to give it more significance. I asked someone there whether love-matches rather than arranged ones are accepted in Afghanistan. He said that they had been for a very long time, but were known to lead much more often to unhappy marriages. I have one student who is 24 years old, whose parents married him off when he was 14, and declares himself very content and proud: he now has four children, the eldest of whom is nine years old. By this reckoning I could be the grandfather. After this ceremony, the future bride and groom are permitted to speak to each other for the first time, though still not without the company of others, and they are able to call the wedding off in the next weeks if the prospect seems too dreadful; though this is a very scandalous course of action, not engaged in lightly.

Afterwards, the guests pick up the plastic bouquets, the music strikes up again, and everyone moves onto the dance floor spinning around with the bouquets held aloft. I joined them. As we were dancing, the curtain in the house overlooking the garden was moved aside, and for the first time I saw the faces of some of the female guests peering out to have a look at the chaps. I waved briefly at them, but was quickly told that that was not permitted, though it was said in a very forgiving way. They know that as a westerner I am on my way to perdition already.

I was privileged enough that same evening to be given the opportunity to compare Afghan celebratory ritual with our own. I was invited to a party given by AWCC, the Afghan mobile phone company (run by foreigners of course), and very reluctantly I went along with a group of young English women I have met here. There was a barrel full of beer, awful canned music, predatory men and graceless women who seemed to screech a lot. After the restraint and meaningfulness of what I had just witnessed, it seemed very hollow, with the drink and the screeching designed to conceal the deceit. I got depressed very soon and left after ten minutes, so I don’t think I shall be invited again. With some sterling exceptions, the banality of many foreign aid workers is one of the many revelations of this visit. One would have thought that danger and humanitarian commitment would suggest rigour of character, but it is not so. I have been to three gatherings of ex-pats since I have been here and each time I have regretted it. Almost everyone is uninteresting, and also uninterested in Afghanistan. They view Afghanistan as a disaster area, a void in desperate need of reform from the West. We should only congratulate ourselves that we are not as they are, and also congratulate ourselves on our freedoms that permit us to do what they can only dream of doing. In fact I find that despite the devastation of the country, we foreigners become more insubstantial when set alongside them. Maybe I idealize, but it is what I feel.

I suppose there are few countries in the world where one can observe Muslim social forms in as unadulterated a form as they are in Afghanistan, especially now that the fall of the Taliban has removed a contrived Puritanism from its practice. I must say that the more I see of it, the more I am impressed by the grace of its ritual and also the kindness and civility with which most people seem to live out its requirements. At its heart is a living adherence to a guiding faith, which enjoys whole-hearted assent by all, so that you truly feel that God is at the centre of men’s occupations. This is shown to me daily in countless different ways. As I said before, I am now living on my own in this guesthouse (a state I am not unused to), but my Afghan acquaintances are very concerned that it will make me ‘deq’ (sad), though it is only for a week. In Afghanistan no one lives alone. It is frowned on for a son ever to leave his father’s home (his wife will come to live with them when he marries), so a wife will live with her husband’s parents. I am sure this can be a very miserable experience, especially for a young girl to find herself at the mercy of her mother-in-law, but it certainly indicates how living alone is considered a state of gross egotism and social failure. In fundamental ways I find social expectations here a deep criticism of my own life, and I am prepared to acknowledge it—the assumption of superiority by most foreigners here is a real blindness, I think. Here, to be unmarried and childless at my age is simply an offence before God and worthy of the mockery of your fellow man. To earn a salary when you have no dependents is also deeply wrong: ‘Who do you earn your money for?’ is a frequent question. Of course I can explain the differences in Western expectations and they will listen indulgently, but they shake their heads in commiseration. The whole concept of one’s ‘personal journey’, to which the West ascribes such value, has no meaning for people here. There is only the one journey, the ‘sunnat’, and your life is assessed according to the extent to which you follow and fulfil its precepts. I come from a broken home, and according to the Afghan, that implies a broken self, for the sins of the fathers are visited upon their sons, and it is right that it should be so. They do not have the same idea of the individual redeeming the many: the people as a whole find salvation, not as individuals, and thus anything that threatens the unity and cohesion of the family is the most sinful and intolerable act there is. It is a hard lesson, but it cannot be evaded here in this context, and I confess that for me it has the savour of truth, though maybe I am also relieved that I am not asked to live it. I don’t know.

On a less elevated level, I have come across some interesting etymological and scatological origins here. First there is the Greek word ‘poustis’ (a homosexual), which comes through Turkish from the Persian preposition ‘pusht’, meaning ‘behind’. I think no further elucidation is required. There is also the well-known Turkish word ‘kro’ meaning ‘a rude and vulgar fellow’, which is derived from the Persian slang ‘kerok’ for ‘large penis’. I find this all very fascinating. My informants are Afghan acquaintances, who seem to laugh about the same things as everyone the world round, and are often quite witty too.

There is much more I would like to tell you about, but I am sure I have tried your patience enough. I am more than happy for you to forward these emails to others, though I don’t know how women would react to the last paragraph. In Afghanistan, vulgarity is strictly a male preserve, as indeed it should be—we are so good at it. And I would not like to be diminished in anyone's eyes. However, if you are able to discuss smegma with Liadain, I suppose I have nothing to worry about. Use your inimitable judgement.

I hope all is well.

Yours,

Andrew

October 17, 2003

To Kristen with Gratitude

"You're funny. You should hang out with us at lunch."

Thus it all began.

Thanks from a huge white whale, Kristen. Happy Birthday.

Kabul Letter Number Four

September 2, 2003

Dear Thomas,

At 3:30 this morning, we were woken by a strong but thankfully brief earthquake that shook the houses for about three seconds. I immediately assumed it was a bomb, as I attended the UN security briefing on Sunday where a British military type with a very loud voice informed us that there is gathering evidence that the Taliban (whatever that really means) are approaching the climax of a long-planned terrorist attack on Kabul. He advised us to avoid places where ex-pats gather in large numbers (I need no security officer to tell me that), and to be remain vigilant. There has also been a sudden influx of soldiers onto the streets, checking bags and flagging down cars. Last week the Interior Ministry announced that decorative curtains around the rear windows of cars have been banned, something which causes much grief to Afghans, who take great pride in adorning their vehicles; never have you seen such richly appointed lorries. I have seen drivers protest in vain as soldiers brutally rip out their automobile curtains. I guess this is so forces of darkness cannot seek shelter behind them.

Despite all these omens and portents, things remain calm and generally very pleasant. In fact, the hint of danger in the air is something I am ashamed to realise I quite like, as long as it does not actually involve murderous gangs bursting into my room. The guesthouse I am living in has given me a radio phone with which to report my movements to a central office, but I find this an intolerable invasion of privacy and have decided to pretend that I never go out. My codename is ‘Tango 3’, which is not very inspiring. If it was ‘The Scarlet Pimpernel’ or ‘Darth Vader’ I would certainly use it, but they have not allowed me those. In fact the only other resident of the guesthouse has gone on holiday to Turkey, so I have the whole place to myself, with only Abdul the cook and two cleaning ladies to look after me. They have promised to protect me when the Taliban show up.

In the meantime I have a new student, and I am rather intrigued at the prospect. He is the new Afghan Minister of Agriculture, which sounds harmless, if not dull; but he is also an ex-warlord of the Hazara Tribe, a Mongol people who apparently are descendants of Genghis Khan known particularly for their cruelty in a country that has had more than its share of that. The Minister himself is supposed to be personally responsible for thousands of deaths—in very imaginative ways, particularly by locking people in metal boxes in the desert for a few days, making them turn black. I think I shall correct him sparingly. I wonder when he developed his interest in Agriculture. We have only had one meeting and he seemed perfectly genial, even modest, and very apologetic about his English. I asked him if he had taken lessons before, and he said that he had been too busy fighting—which I felt was a reasonable answer.

I got an email the other day from my Great Uncle Douglas (who had an affair with Melina Mercouri during WWII) and it appears he was stationed on the Khyber Pass in 1946, which is just down the road from here. Apparently the Afghans were considered very wild and dangerous in those days. How times do change...

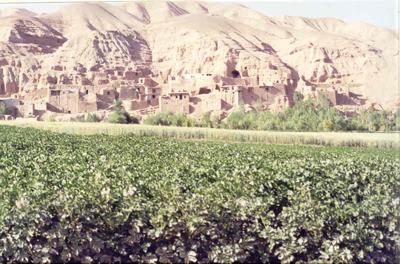

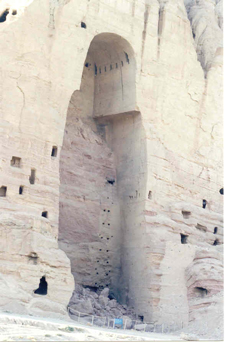

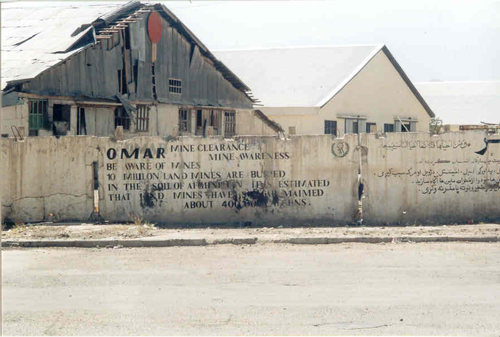

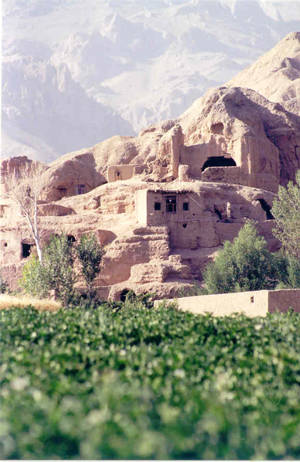

Last week I had a wonderful day travelling to the Panshir Valley, which is about 150 km north of Kabul, and stretches 100 km into the Hindu Kush. It has become famous over the last twenty years for its dogged resistance to the Soviets, who tried on seven separate occasions to subdue it, and also to the Taliban. It is the homeland of the Tajik tribe who are now top dogs in the new Afghanistan, although the Ministries are supposedly shared out fairly between all the factions. I went there with Razoul and one of his cousins (of which he has about fifty); it only took about two and a half hours to get there on a rocket-scarred road. Afghan driving is something to be experienced. It involves giving no quarter and pressing on regardless: quite bracing. The road is lined with white or red markers indicating whether the surrounding area has been cleared of mines or not. Razoul himself worked as a mine clearer for a year, and told me of his terror the first time he located a mine and had to remove the covering earth by hand. He is a very calm and philosophical person, but every so often he will tell me a story which speaks of a very different path through life, like seeing rockets land in the market place, or selling guns when he was eight years old.

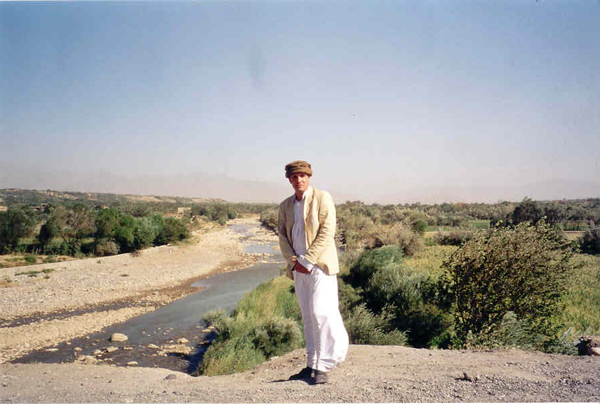

The entrance to the valley is very narrow and is still guarded by a burnt-out Soviet tank, a token of the vanity of Ozymandias. Before entering we had to report to a group of stern Tajik soldiers bristling with guns, who were delighted to have their photographs taken. I wore my Afghan clothes for the day (as a security measure), and they all had a good laugh about that, though I think they liked it in fact. The valley itself broadened out into a wide green plain lined with villages of mud houses, with the mighty Panshir River running down the middle. It was a stirring landscape, and there is no question that in the magnificence of the mountains the constant tension of living in Kabul and being caught between such irreconcilable cultures dissolves very noticeably. Working for a western agency is not the way to see Afghanistan. We drove as far as the tomb of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the leader of the Tajik Mujaheddin, who is now the presiding genius of Kabul, and a sort of romantic hero. He was killed by an Al-Qaeda suicide bomber on the 9th September 2001, which is now thought to have been a prelude to the attacks on New York City two days later. It will be marked next week as a national holiday. He is buried on a hillside at the widest point of the valley, a wonderful location for a hero, if that is indeed what he was. Not all agree.

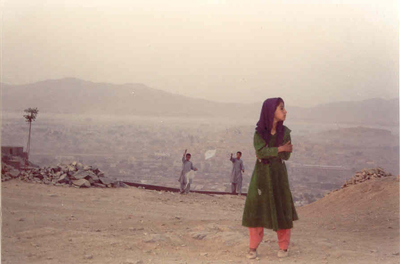

Yesterday I went to visit the mausoleum of the present king’s father, who was (like many Afghans it seems) also assassinated in 1933, which gives you an idea of how long the present man has been king: he was crowned the same year Hitler came to power. The building is on another hillside overlooking Kabul, and must have been quite fine once, but is now terribly damaged by artillery fire. The cemetery around is also full of smashed gravestones and rocket shells dug into the earth. Opposite it lies the Bala Hissar, the old fortification where the British occupying army were all killed in 1847, including their wives and children. A sort of 19th century Twin Towers? The British then came back and pulled it down. The mountains stare down from all directions dry, dusty and ancient, and the mud houses seem to merge into the soil, a perfect example of architecture in harmony with the elements. It a harsh place with no disguise or contrived compensating sweetness. It is very difficult to return from places like this to gatherings of other Europeans—you feel even more insubstantial than usual. In fact, I think Afghans might feel equally diminished in their encounters with westerners. Side by side the two cultures mercilessly expose each other’s failings, and contrive to make the other look foolish, though unfortunately I think we come off worse in the end.

I must emphasize however that my relations with local people are remarkably good. People stop and wave on the way to work, and shout out things like ‘Hello mister!’ and ‘Welcome to Afghanistan!’. I think the bike goes down well, as most foreigners travel in 4x4s with darkened windows. What I like most, however, is my class of architectural restorers. Today I learnt that one of them, Abdul Jalil, is member of a Sufi tariqua, and it comes as no surprise as he has a strikingly serene, wise and selfless manner. After I expressed interest he started to explain the history of Sufism in Afghanistan, starting with a description of the various branches of Islam. The one Shiite in the class (a Hazara, for the Hazara are Shia as well as Mongols) pointed out that he had omitted the Shia, and he very graciously apologised and let the other continue the story. Given that the Tajiks and the Hazara were killing each other until very recently, I found this quite a moving moment. I asked Abdul Jalil whether the Sufis live in communities apart from society, and he said that they deliberately did not: ‘They must live with other people, they must pray at night and work with others during the day. In Islam it is very bad to live apart, it is not the right way.’ So there you are. I also asked him about television, and he said it was possible, but one must be very careful. He himself did not watch it.

He also told me a nice story about Nasruddin Hoja, a mediaeval mullah and wit. A friend found him one night peering at the ground under a gas street lamp. ‘What are you doing, Hoja?’ he asked him. ‘I have lost some money,’ he answered. ‘Oh, where did you lose it?’ he inquired. ‘Over there, in the garden,’ he said. ‘Then why are you looking for it here?’ the other asked in surprise. ‘Because the light is better here,’ said the Hoja. Apparently this illustrates the vanity of looking for the truth by the light of reason alone, for you will look in the wrong place. Abdul Jalil seems to be struck by my interest, and has offered to take me to a meeting of Sufis before I leave, which is what I have been hoping for. This man exudes a strong sense of authenticity, and the others in the class seem to be correspondingly respectful as well as affectionate towards him. I am glad that he is the one who has offered to accompany me. I shall share what I learn with you.

I am now planning to return to Greece overland via Iran. The language I am learning is more or less what they speak there, so it should stand me in good stead. I also have a former student in Iran who has offered to put me up in Tehran. From what I read in the guide books it sounds fascinating, and I know I will like it very much. But there is no guarantee I will be given a visa; unfortunately England is a little too friendly with the Great Satan. We shall see.

Now I must return to my empty guesthouse. I hope all is well with you.

Much love,

Andrew

October 16, 2003

Kabul Letter Number Three

August 14, 2003

Dear Thomas,

I hope all is well, and that the summer passes sweetly. I have just come from my first Dari (Afghan Persian) lesson with a new teacher, an older gentleman who happens to be my friend Razoul’s uncle, and who was recommended to me as knowing all you need to know about Dari. Unfortunately he knows almost nothing about English, which makes the lessons a little difficult at this early stage. He also has six fingers on his right hand—another thumb, equipped with a nail, emerges from the side of his proper thumb—and I find it difficult to avoid staring at it too fixedly during the lesson. I have read about such things before—Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s second wife, for whom he rejected Rome, is said to have been similarly afflicted (yet he embarked on the Reformation for the sake of her beauty) and this was used as proof of her witch-hood when he tired of her and decided to get rid of her—but I have never seen it before. I guess in the West we get cosmetic operations in early infancy so our employment prospects will not be affected. In fact, I think it is precisely because he has six fingers that makes me want to keep him, even though he is actually not a very good teacher.

So much for language. Now transport. I am enjoying my excellent new Indian bicycle, manufactured by HERO of Bombay, which gives me new freedoms around Kabul. Afghan drivers are particularly erratic and wilful, however, and one has to stay alert. You often see an Afghan transporting his whole family across the city on one bicycle (one child on the crossbar, wife in burka and child on the back) so I can justify risking only myself. Women, of course, never ride bicycles, and if a western woman were to do so, she’d be greeted with much mirth from the locals, at seeing someone lose sight of themselves so grossly.

Yesterday I went to the tailors to be measured for my ‘perantonbon’, the long cotton shirt and baggy trousers worn by most Afghans and Indians. In fact I had to go to two tailors, one for the clothes, and one for the decorative embroidery around the collar which is distinctively Afghan and costs more than the rest put together. The tailor shops had a number of 12-year old boys working in them, which no doubt should cause outrage, but I’m afraid I didn’t feel it. At least they are doing something useful. They will have a trade and won’t spend their adolescence working out their particular ‘thang’. I don’t think Afghans really have adolescence: they are children and then they are men—and very soon after that they are fathers. For us, of course, adolescence lasts about thirty years. I’ve decided to get the perantonbon in protest against the unspoken assumption (of Afghans as well as others) that western clothes are where it’s at; certainly anyone wishing to work in a Ministry or top company would be expected to wear western clothes. One of the things I most like about this place is that most people don't dress like westerners, so I am going to teach in their dress as well, even at the awful United Nations compound, about which more later. Of course, an ageing Englishman in a perantonbon will be a very foolish sight, but I am prepared to offer that up as my own personal sacrifice. I also think they look wonderful. The turban is next.

I am increasingly sceptical about the whole western presence here in Kabul. There are a lot of armoured cars with German soldiers in sunglasses trundling through the city—though I think they really do stop Afghans killing other Afghans, which is probably a good thing. It is more that the repulsiveness of so many of our western ways stands out in much starker relief here. Yesterday I had to go to the ‘Supreme’ supermarket for booze, an out of town western supermarket next to the British base, with ancient bare mountains all around. A line of black four-wheel-drive vehicles stood outside, containing westerners eager to stock up on life’s little treats, guarded by two Dutch soldiers in a miniature tank, as impoverished Afghans wandered past. A sign said Supermarket: Weapon Unloading Station—they don’t have those in Oxford. I had Razoul with me, who is rather devout, and I was very embarrassed, nay humiliated, to spend $100 on alcohol when that is more than his monthly wage. I apologised to him afterwards, but I think they just think that the rich and profligate white man is as inevitable as dust in summer. In fact I have managed to live quite a frugal life here, as I am very conscious of the great poverty all around us, and I haven’t smoked a cigarette since I arrived, which has been strangely easy. What does that say about my addiction?

The worst thing, however, has been the United Nations. I teach a middle-aged Italian woman from Rome called Carla, who is actually in charge of prison reform for Afghanistan. The U.N. has given different countries different areas in their great ‘development drive’, and Italy has been given ‘The Law’. This is like giving Greece ‘Road Safety’. Carla is actually a prison governor in Italy, so she has a tough outer shell, but she is also deeply paranoid and full of complexes, and has taken to crying in my lessons because ‘the others’ are out to undermine her and the Afghans don’t want a woman in her position. This could have been foreseen. She also has to conduct all her business in complex English, which she is years away from mastering—she talks like Chico Marx—and she shows me e-mails she has sent to UN headquarters that are frankly incomprehensible. If she had a real sense of honour she would recognise that she is not competent to do this sensitive job in a country which is in deep need of real help; but she most likely earns more than $150,000 a year, so I expect she will stay the course. I teach her in the U.N. Club, where waiters with trays of cocktails swish about by the swimming pool, an awful atmosphere of people with too much money checking each other out. In the context of Afghanistan I find it particularly depressing, and always leave feeling tainted. Apparently, the U.N. is known for its vacuum-sealed money-driven presence wherever it intervenes around the world. But of course there must be good souls amongst them. The strange thing is that in this country that has just gone through twenty-five years of bloody revolution, occupation and civil war, it is the European who is the most neurotic and unstable of my students.

My class of Afghan architects is something quite different. They are kind, intelligent, ironic, aware, sensitive and comic. I like them very much, and sometimes find their palpable goodness very moving. On top of this I often arrive to find them doing their prayers in the office before class, for we start at 5 o’clock. This devotion is accompanied by no trace of fundamentalism, nor do I feel like I’m being judged, although I suppose their adherence to their faith is unquestioning. There is also something about the Persian physical type that I like very much: with their piercing hawk-like faces, each of them looks like a prophet.

On Tuesday we went to the open-air cinema at the French cultural centre, a regular meeting place for Kabul ex-patriots. The air was thick once again with that urgent need to present one’s own special and unique individuality to the crowd, which is so absent from Afghan society. It seemed fairly absent from Greece too, when I first went there. The film was called ‘Arizona Dream’ with Johnny Depp, Faye Dunaway and Jerry Lewis. It was a sort of crazy film that was neither clever nor funny, except for some wry spoofs on older movies. I found myself watching it with what I imagine was an Afghan eye, and found it really very offensive and full of hollow arrogance, full of assumptions that I don’t share at all. I suppose it wasn’t much of a film, but it only reinforced my ever-growing sense of our cinema as an agent of a darkness. I couldn’t wait for it to finish and go home.

I’ll soon be talking myself into joining al-Qa'eda, so I guess I should stop now. In the future, I will try harder to write about the many good and positive things about being here. I am constantly aware of those great dry ancient mountains out there, harbouring an unchanged way of life. I hope I will get a chance to go before too long. But of course the Taliban are still out there too, and they don’t like us too much. Hence the turban.

Lots of love,

Andrew

October 15, 2003

Kabul Letter Number Two

August 11, 2003

Dear Thomas,

All is well, despite a slight stomach upset and a general tiredness caused by the shortage of oxygen, which I am still not used to. I am also woken every morning at 4.30 am by the call to prayer. ‘Prayer is better than sleep,’ which is true, but I never really get back to sleep.

Yesterday was the most interesting day yet. Our driver Razoul, who is becoming a friend, drove me south out of the city to the former Royal Palace of the former king, who was crowned in 1933 and is still alive and now living back in Kabul. It is a ruined shell, but still a grand building. The avenue down to the Palace is lined with destroyed buildings, as this was one of the most the most heavily fought-over areas. It is also where the Hazara people live, who are a Mongol people said to be the descendants of Genghis Khan’s Golden Horde. This makes them stand out in what is mostly an Aryan country. They are also Shiite, and they have always been seen as outsiders by other Afghans. Under the Taliban a slow policy of extermination was implemented against them.

Razoul also took me to his old school. It had been used as a base for fighting during the war, and there are traces of mortar attacks everywhere. Bullet holes still grace the walls. I even saw a Russian shell-casing lying on the ground. All the windows have been blown out, and people have come to remove the electric wiring, in order to sell it. The extraordinary thing is that the school is still in use. The classes have timetables on the walls, with Physics, Biology, English and Arabic all being taught in the ruined premises. Razoul said that when he was a student there, there weren’t any chairs and he had to crouch during the lessons. We stood in this ravaged building and the mountains stretched into the distance all around us, great bare silent witnesses to the brutality that the Afghans have meted out to each other. In many ways the best thing about this visit was to see the land stretching away into the distance: Kabul quickly becomes quite claustrophobic, with the dust and the smell and the people, and it was good to be able to lift my head up at the mountains.

From the school I saw a completely contrasting sight nearby, a very large walled garden at the foot of one of the nearer hills, with rows of flowers surrounded by a long wall of pointed arches. These are the Gardens of Babur, which contain the grave of Babur, the founder of the Moghul Empire and the greatest Afghan in history—though in fact he wasn’t an Afghan at all, but an Uzbek. He was a descendant of Tamerlane and originally came from the Ferghana Valley in Uzbekistan. He was denied his inheritance in his youth, so he travelled south to Kabul and captured the city. From here he invaded India and went on to create an Empire that stretched to Calcutta, with its capital at Delhi. Kabul remained his greatest love, though, and after he died he asked to be buried here. He gave instructions that he have no tomb, for he wanted flowers to grow from the earth that held him, but his grandson constructed one with the following inscription:

‘Only this mosque of beauty, this temple of nobility, constructed for the prayer of saints and the epiphany of cherubs, was fit to stand in so venerable a sanctuary as this highway of archangels, this theatre of heaven, this light-garden of the God-forgiven angel king whose rest is in the Garden of Heaven, Zahirrudin Mohammed Babur the Conqueror.’

The gardens are being restored after years of destruction and neglect. Two of my students are working on the project, and they were there when I visited and invited me for tea in their tent in the garden. Afghan tea is a green tea flavoured with cardamom, drunk without sugar, and is very delicious, much better than Turkish tea. We sat and talked about Afghanistan, about the war, the Russians, how they feel about each other and about the foreigners in their country now. We talked for an hour, so I can’t report it all, but they all said that they were glad to have foreigners here to help them, but if the foreigners begin to use guns to gain power over them, then they will resist them with force. They also said that they didn’t like the soldiers who teased their ‘girls’ (I understood this word as ‘guards’ for a while, and I couldn’t see why the soldiers would tease their guards, but the misunderstanding was cleared up). In fact I find it very hard to believe that anyone would tease Afghan women: it is obviously unacceptable here, and profoundly provocative. But the general message was that foreigners were welcome, and they all assured me that nothing would happen to me here in Kabul; it is only in the south of the country that one needs to take care. We shall see.

After this most interesting visit I returned to the city to teach a lesson to my group of architects and restorers, including the ones I had just seen at the Gardens. This is a class of about ten students, and the more I get to know them the more I discover how various the ethnicities of Afghans are: Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara and others speaking Persian, Pashto, Urdu, Baluchi, Hazaragai, Uzbek and Turkman. In the class there was much laughter and teasing about their differences—I am always aware, however, that they were killing each other not so long ago, and so try to keep a watch on where the conversation is going. Every so often a slightly threatening tone emerges. But it really does seem that the Afghans lived in harmony from about 1919 to 1978, until foreign powers intervened with their money and their weapons, first the Russians, then the USA and the Pakistanis, the Iranians and the Saudis. And the country has suffered terribly. In fact I think this is a very spiritual and non-materialistic people, which must be partly why they were able to fight so resolutely and successfully against the Russians. But the experience of fighting outsiders seems to have given them a taste for it, and led to their fighting each other. The destruction and psychological trauma is very great. Yet I think to have come here in the 1960s must have been quite wonderful. I will try to visit some of the country before I leave.

All for now. I hope all is well.

Andrew

October 14, 2003

Kabul Letter Number One

August 5, 2003

Dear Thomas,

I have now been in Kabul for about 48 hours, and I thought you might be interested to read some of my impressions so far. It is slowly dawning on me that I really am here. The contrast with Dubai, the Mecca of shopping (where I stopped over on Saturday night and was given a three-room suite at a 5-star hotel, run by Indonesians and Japanese) is as extreme as you can imagine—I certainly prefer it here. In fact I wonder if ‘development’ means becoming like Dubai. Our flight to Kabul from Dubai on Afghan Airlines took about two hours, over the Persian Gulf and Iran. Sitting next to me was an Afghan man who now lives in Canada—this was his first trip back for over ten years. As we came in to land you could see the dry desert landscape stretching in all directions, with the low, mud-built square houses which seem to be typical of Afghanistan, a little like the adobe houses of the Indians of New Mexico. As we taxied along the runway to the terminal buildings, you could see the wreckage of military planes, rusting or burnt-out, on both sides. This immediately makes you feel that you are somewhere very different.

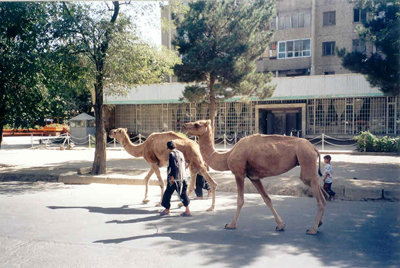

As soon as I got to the terminal building, my friend and employer Tim was there to meet me, along with our driver, Razoul—he, like most of the better educated English-speaking people now getting jobs with the many charity agencies in Kabul, had been living in Pakistan until the fall of the Taliban. The scene at the airport was fairly chaotic, with lots of Afghans in their exotic clothes—I really like the way they dress, especially the varieties of headgear, like the great turbans, and their long flowing shirts. I certainly intend to buy something of the sort for myself, but not just yet. The most curious thing is that a lot of them dye their long beards bright red, which looks quite comic, but I am told it is because black beards are hotter. Most women still seem to be wearing burkas, completely covering their head and body, but some just wear a headscarf and a long outer garment. Eventually we got out into the car, and Razoul drove us into the area of town where I am living. This was my first view of the city. The first thing to say is that it really is much more relaxed than expected; there are not many soldiers to be seen on the streets, and the few American soldiers I’ve noticed look surprisingly inconspicuous. Most men travel by bicycle, with their long robes flowing beside them, though there are a fair number of cars around. Kabul itself is hot but not too hot, and dry, which makes the heat a lot more tolerable. However it is very dusty, so I am constantly thirsty. The least pleasant thing is the smelliness, a sort of constant dull smell of rubbish and sewage; the drainage system is not very up to date. Yesterday I found I was have trouble breathing, and I thought it was because of the smell or the dust, but I have since learnt it is because of the altitude: Kabul is about 7,000 feet above see level, and it takes time to adjust to that. The buildings here are all very low-lying, usually two stories at most. Running through the center of the city is a chain of low mountains. On the other side of the city, the destruction from the fighting is much more apparent, for it bore the brunt of the shelling—rows and rows of ruins and collapsed buildings. The part I live in is more intact, and there are a lot of NGOs and aid agencies based here, usually surrounded by walls with a chaka wallah (gate man) sitting outside. There are lots of small workshops dotted around, usually making metal goods like pipes, saucepans, and kettles, and small shops selling a few basic goods. The picture of Ahmed Shah Mahsood, the Tadjik commander assassinated two days before September 11th, is everywhere. He is obviously the guiding spirit of the new dispensation.

I am staying at the headquarters of TEAR Fund, and we have a cook who comes everyday. He speaks English, as a lot of people do, especially if they have been in Pakistan. People are generally friendly and warm, and I have felt nothing but goodwill from people. And there is none of the hassling that you get in Turkey or Morocco. They greet you by holding their hands to their chest, as though they have taken you to their heart.

There are literally thousands of aid workers here of every description, and not one of them has been hurt in Kabul itself, though in March a Red Cross worker was murdered in cold blood by Taliban in the south of the country. Some of the agencies are very strict about security and will not let their workers walk anywhere until they have been here a month. One has to radio to a central monitoring agency every time one goes out. My boss, however, has a different view of things, and we walk around a lot; last night I walked back to my place alone in the dark. My feeling is that this is the right attitude. There are probably fewer people with bad intentions than in London, and it makes the experience of being here much less insulated. I also believe that people’s intense religious devotion makes the vast majority inclined to welcome and protect the stranger in their midst. There are exceptions to everything, though...

I have just given my first lesson, to a very likeable group of Afghan architects who work with the Aga Khan Cultural Trust. They are working on the restoration of buildings of cultural significance in Kabul, the 330-year-old tomb of Timur Shah and an Uzbek mosque of the same age. Almost nothing has escaped the fighting of the last twenty years, and the idea that they are setting out to restore their buildings in this way is very impressive. I must say that I am increasingly grateful for the opportunity to come here. It is intensely interesting, and quite humbling to see the human spirit enduring and even growing in such difficult circumstances. I am already learning a bit of the language, Dari, which is basically the same as Persian. It is not too difficult, nothing like as hard as Turkish, though there are a number of similar words.

Last night was an unexpected experience. I went with a group of aid workers to a meal at the ‘German Club’. This is a fully-fledged training restaurant providing German cuisine, and the experience of ordering Jaegerschnitzel and Apfelstrudel und Schlagsahne in the middle of Kabul was rather surreal. The strangeness was intensified by the presence of the four commanding officers of the ISAF (International Security Assistance Force), who were having dinner. There were soldiers on the roofs around and in the courtyard, all heavily armed and looking very needlessly threatening. When they had finished their Apfelstrudel they were quickly bundled into the waiting military vehicles and hurried home to bed.

Hoda hafez (God with you),

Andrew

October 10, 2003

A Homeric wine-red sea

Last night there was a spectacular thunder storm. From my experience, only Greece can put on such a thrilling lightning display. There is little wonder why the ancients placed the god of lightning at the top of their pantheon. Once last Autumn during an evening dinner party in northern Euboia, where I live when I am not in Athens, there was a thunder and lightning storm of such intensity that one of the lady guests was forced to cover her eyes with her fingers and stick her thumbs in her ears. Another lady, a special friend, had quite the opposite reaction. The Aladdin lamps had all blown out from the ferocity of the wind, and in the dazzling brilliance of the lightning flashes, coming one after the other in rapid breathless succession, I could see her face, the years wiped away, eyes wide and alive, a hint of smile on her open mouth, each flash driving a wave of pleasure down her arched back and through her whole body. Aphrodite born, the power of Zeus enticing her motherless out of the sea foam.

Across the street from the ruined Temple of Olympian Zeus stands an imposing concrete Best Western Hotel, where I stayed when I first came to Athens, what seems so long ago to me now. A travel agent in London had booked the room for me—she thought it better not to stay in a hostel the first night in a new city. Her commission was no doubt flashing behind her eyes as she said it, but it was probably all for the better, as I’ve subsequently heard that the Athenian hostels also pass for homeless shelters. My plane arrived before sunrise that morning, so when I got to the hotel, with surprisingly little difficulty, it was too early to check in. I left my pack in the lobby and went exploring. Turning off the main street, the torturous Andrea Singrou that goes to the sea, I wandered the side streets, where I soon encountered a lovely little church. A man was on the steps, who struck up a conversation with me after I had ducked inside for a minute or two. He is my first real Greek, I thought, and happily accepted his offer to take me to his pub, as he called it, where I supposed I’d join someone named Zorba in a couple rounds of ouzo. The pub turned out to be a dark tiny bar, where two older women hustled stooges like me, the bill for their overpriced drinks extorted by a muscleman who was probably half-Turk. That was my first experience of Greece, those were my first real Greeks. I left a hundred dollars poorer.

There have been worse first experiences of Athens. A dear friend was even younger than I when he first arrived on a crisp winter’s day, without a place to stay or really any idea where he was. A nice well-dressed gentleman approached him and said, ‘Oh, you can stay in my place,’ and my friend, God bless him, agreed. When they got to his well-apportioned flat, there was a suspicious click of the front door lock, followed by a lovely dinner with lots of drink, the gentleman fondly describing how he too likes this movie or that, how he finds Ella enchanting as well—physically like-minded to all my friend’s tastes and dislikes, with a little press of the shoulder here and a little ‘I’d like to kiss you’ there, until the gentleman went to the toilet and so gave my friend a chance to escape. Luckily he had seen where the key had been put.

The Mediterranean is dark like that, dark and calm and often wine-red. Its stillness is at first unnerving to a Californian, only familiar with the restless crashing Pacific. One can swim in the Mediterranean, really swim. But in summer its stillness makes it tepid, like a bathtub, no relief from the heat.

October 09, 2003

Careening through Kabul, dreaming of Chalkida

Athens wasn’t always like this, with the noise and the smog and, above all, the concrete. The walls of nearby tavernas are adorned with pictures showing Athens as it used to look. One of them, my favorite, is a photograph from the 1920s. It shows Singrou Street, which runs from the Temple of the Olympian Zeus to the sea: palm trees one after the other trace what was then a modest dirt road. In the distant background one can just make out the Acropolis and a few large houses here and there surrounded by olive groves. Now the street is a concrete canyon, loud and nightmarish, the trees long since cut down, its seaside destination devastated by pollution.

To prepare for the 2004 Olympic Games, Athens has decided to try its best to clean up the Saronic Gulf, which is nestled between the southwest coast of Attica and the northeast arm of the Peloponnese. Greek ship owners have had their way with the Saronic Gulf since Pericles’ Athenian navy controlled the eastern Mediterranean seaways as far away as Egypt. The harbour of Piraeus is a sight to behold—it would be difficult to find a greater number of massive sea vessels gathered in one place. During the years of Pericles’ rule, the Golden Age of Athens, a limited democracy at home controlled a growing fragile empire abroad. The Persians had tried to conquer Greece, and to defeat them the Greeks united for the first time by forming the Delian League, tacitly authorizing Athens and its navy to assume the leadership. Tribute money poured in, but when the Evil Empire was defeated and Athens sued for peace, the system was not dismantled, and the other city-states, especially Sparta, grew uneasy with the status quo. The monuments of Athens, its leisure and its democratic sophistry, made the rest of the country turn green, then red, and finally, after many decades of trying, Sparta smashed the Athenians and burned its navy, to the last ship. Athens never recovered its political power, not until 1821, when the Greeks rose the standard of revolt against the Ottomans and, in a fit of confused nationalist zeal stirred up by Napoleonic France, made it their new capital. Greek ship owners still rule the merchant waves, only now they fly flags of convenience, their masts pledging allegiance to Panama or the Ivory Coast.

The government in Athens can do little to help the Saronic Gulf, though they are desperate for their Olympic visitors to be able to swim without getting cancer. The best they’ve been able to do is reroute most of the sources of land-based pollution eastwards around the tip of Attica, where a strong northerly current drives it all into the Euboian Gulf. Dolphins use this current on their long road to the Black Sea. I have witnessed what must have been thirty or forty them, follow boats up the Euboian coastline, flitting back and forth before the prow, turning on their sides to sneak a one-eyed peak at the euphoric faces hovering in the air above them. When I am not sharing a flat with my boss off Kolonaki Square, I live on that coastline, and swim in its water—though they say that in seven years it won’t be fit for swimming, not even for dolphins.

The dolphins’ watery road, before it passes into the northern Euboian Gulf, squeezes through a narrow channel between the mainland and the island of Euboia at a city called Chalkida. A number of wooden drawbridges have spanned that channel, and the current below it is called the Mad Waters, and if the local auto mechanic is to be believed, who traveled the world seven times over as a Greek merchant marine, every six hours, from time immemorial, the water’s flow inexplicably changes direction, first flowing north, and then south, and then north again. Many a Greek graduate student has tried to decipher this mystery, from Aristotle onwards, who is said to have thrown himself off the bridge into the sea below, in despair over his inability to solve its riddle. A massive gray suspension bridge now ferries travelers across his peripatetic deathbed, but they do not look down for fear they might set their eyes on the largest cement factory in the Balkans, which sits snug and gruesome on a man-made island close by. Titan Cement has built concrete apartment blocks for its employees, downwind of the factory, but the green of thumb are advised to apply elsewhere: nothing grows there.

In the mid-1800s, an Englishman wrote that travelers to Greece need see only two places: the Acropolis of Athens and Chalkida. Chalkida today is a dump; nobody goes to Chalkida. Its turreted Ottoman stone walls are torn down, its 1920s-era bungalows replaced with, like everywhere else, six-story apartment blocks. I’ve been told that in the quiet of the early morning, a coffee at a seaside café can inspire tears, so beautiful the water there can be. But an architect friend of mine, who comes from Chalkida and has for years struggled in vain to convince his colleagues in Greece of the importance of natural materials and aesthetics in architecture, threw up his hands in disgust last Spring and moved to Finland, where he says the people are more sensitive to these things.

They are also the world’s heaviest drinkers. During a visit to Helsinki in June, I visited a local sauna, where they beat me with birch sticks, and where women in white smocks walked nonchalant amongst the golden bodies of naked men and boys. Like the waitresses in American diners, these women are strong and fast-talking, and no doubt, in their sing-song Finnish way, they call the men hon’ as they massage them, and let ring a “Y’all come back now, y’hear?” as the men make their way home, clad only in loin-cloths, back to their wives with the many-voweled names. After the sauna, I accompanied some journalists on their rounds of Helsinki’s nightlife hotspots. We went to a penthouse bar in the city’s tallest building, where the balcony is surrounded by a plastic barrier taller than a man—Finland has the highest suicide rate in the world, not surprising considering it is plunged into darkness seventy percent of the year. Afterwards, we went dancing in a club that looked as if it had been furnished by Ikea, to music without even a trace of melody, just thumps and boinks and the other two sounds that make up Scandinavian pop. Twenty-somethings in suits moved awkwardly on the dance floor, not having bothered to put down their drinks. Two in particular honed in on one of the girls in my party, and approached her zombie-like before pointing, rotating and collapsing to the floor dead drunk.

Finnish is considered the world’s most difficult language to learn by many linguists, and is a member of the Finno-Ugritic language family, related directly to Hungarian and less directly to the Turkic languages. It has something like thirty-eight cases or declensions: something absurd like that. I know an Englishman who can speak twelve languages fluently, but after spending three years in Turkey can still only just follow a basic conversation. He returned to Greece yesterday after six weeks in Afghanistan working as an English teacher. He is one of those rare types who are only themselves whilst outside their homeland. I’ve watched him amongst true Brits, and the rapid transformation he undergoes in response to them is remarkable. Everything changes: he sits up straighter, begins to drop his alma mater. But in Afghanistan he went native, like a modern-day Lawrence of Arabia. He threw off the western garb of the U.N. peacekeepers and World Bank economic strategists, went to a local tailor and got a full Afghani set, turban and all. He then bought a bike and careened happy and free through Kabul, glad to be British, always glad to be British as long as he's outside Britain.

The noise from Kolonaki Square

My boss was not in the apartment when I got up late this morning. I sleep in the living room, she sleeps in the den opposite. I had been lying awake for some time. In fact, it had been the sort of night when one wonders if one has slept at all.

Athens is always noisy, even in the chic neighbourhood surrounding Kolonaki Square. With the exception of the eerie hours between three and five, when the nocturnal noisemakers who are the reason why Nescafé is the so-called Taste of Greece! finally click their way home; until those brief two hours, by which time real sleep is out of the question, the streets six floors below send up a countless number of squeals, thumps and chirps from the mopeds and the Euro-pop and those Mediterranean conversationalists who struggle and succeed to be heard over all the noise. The first encore is at five o’clock, when the city’s antiquated garbage trucks begin their rounds (there is a dumpster on every block here); and the second, destined to last until mid-afternoon, begins at seven, when the racket of electric saws and jackhammers rises with the sun, the sounds of Athens’s ceaseless construction work, the terrible curse of cities built entirely of concrete.

There are roughly five million people in Athens, half the population of Greece. There is no opportunity anywhere else; Greeks like it that way and have done for a hundred years. Yet, to them Athens is not The City, not like New York is for the New Yorkers or San Francisco for the San Franciscans. No, for the Greeks—even the common Greek who is hardly aware of what he means when he says η Πόλη—the City above all cities will always be the city of St. Constantine the Great, Emperor of the Romans: Constantinople, New Rome, their city, their destiny. Its modern name does not undermine their claim. As the Turks marched slowly westwards, all those centuries ago, they came across sign after sign reading To the City, Εις την Πόλη, Is-tan-bul. And tell a Turk you come from Greece and he will exclaim, ‘Ah! Rum!’ which means, ‘Ah! A Roman!’

In the Author’s Note at the beginning of his novel Julian, Gore Vidal writes in reference to the times of Constantine and his immediate successors, ‘For better or for worse, we are today very much the result of what they were then.’ In a time when a cinematic action hero can use bread and circuses to convince the mob to give him control over the world’s seventh-largest economy; and when war and famine are overshadowed in people's minds by the mauling of a homosexual magician by a white tiger; well, in times like these, Vidal’s statement seems very near the mark.

In Washington D.C., a sign celebrating the city’s two-hundredth anniversary reveals what George Washington wrote to its French designer, the same man who would go on to design Napoleon’s imperial Paris (and I paraphrase): ‘It should be a majestic city with wide avenues and grand buildings, as befits the capitol of a Great Empire.’ A mile away a glimmering statue of Thomas Jefferson stands thirty feet tall, surrounded by Corinthian columns and gold inscriptions that eulogize the hand of God so clearly at work in America’s destiny. Constantine stole the famous statue of Apollo from the temple at Delphi and set it atop a pillar at the center of Constantinople’s forum, though not before knocking off its head and replacing it with his own bust in marble. The statue fell down one stormy night just before the Turks launched their final successful siege of The City, but the pillar can still be seen, covered in black from air pollution, a landmark that now reminds veiled window shoppers to turn right for the Grand Bazaar.

The Romans of Constantine’s time licked their lips over Mesopotamia, its golden waves of grain as irresistible a temptation for them as its black gold is for the Romans of our day. Constantine died before he could overthrow the Great King of Persia. Though his nephew Julian the Apostate was able to bring Persia to its knees, nevertheless he was in the end too greedy and ambitious to accept the Great King’s generous peace-terms. His overwhelming military advantage slowly deteriorated as his soldiers starved before the gates of Ctesiphon, picked off one by one by Persian guerilla fighters. Without an exit strategy, and unable to keep the troops interested in his moralistic revivalist religion, Julian was speared through by his own bodyguard, and his incredible territorial gains were soon lost by his successor, the drunkard Jovian. Our own emperor is not the philosopher Julian was, not by a long shot, but still he follows in his predecessor's footsteps.

The Romans never conquered Mesopotamia. That job was left to the newly Islamicized Arabs who burst from the desert and conquered the world in something like five decades. They razed Ctesiphon to the ground, and built a new city called Baghdad nearby. When their conquests reached Spain, they imported palm trees from Egypt and built as enlightened a civilization as probably ever has been, one of such brilliance that even the Christians, intoxicated with the new language from the oases, turned their backs on Latin and translated their liturgies and their church fathers into Arabic. Eventually, northern barbarians used gunpowder to impose the Pope on them, and erected the first modern police state. Arabic was outlawed along with Jews and Muslims, and knighted lovers of books and learning madly pined for the old days and its glories; they jousted with windmills and wrote fantasy novels about an imaginary utopia they called California. Some of the victims of forced conversion went to a newly discovered India across the sea, where they found the California they’d been reading about. They brought their palm trees with them, and their courtyards, and their aristocratic yearning, and settled down to stay; unfortunately so did the barbarian Jesuits with their secret service ways; and then came other barbarians, of the Washington variety, and the last vestiges of old Cordoba disappeared. The palm trees remained, and the longing for utopia, but not much else.